More from the series of lecturettes from old and/or defunct classes. This is the 5th lecturette from DU’s defunct Writers on Writing course, which was for creative writing students in their graduate Liberal Arts program at University College.

————————————–

The POV Conundrum

There’s more wisdom in a story than in volumes of philosophy. –Philip Pullman

Last week in Introduction to Fiction at Metro, I discussed “The Tell-Tale Heart” with a handful of college freshmen. They all agreed that it was the most entertaining story they had read so far this semester, but were uncertain as to why. Something about the immediacy of it, they intimated: there was an element of suspense in “how Poe wrote it,” or maybe it was his “writing style.” What is his writing style?–I asked. They didn’t know: what does “writing style” mean? Is it the choice of words, the breadth of vocabulary, that ever amorphous term “voice,” or what?

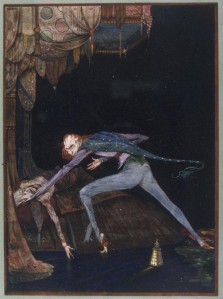

The conclusion we reached had to do with Poe’s POV-character voice. They were surprised to find that nothing actually supernatural occurred in the story (having heard of Poe but having never read any of his work before now). At least, the eerie spooks they all expected were all in the narrator’s head, not real in the world of the story. They were also surprised that it wasn’t suspenseful because of it being a mystery story, either–I mean, we all know who dunit and how he dunit, there was no detective lifiting fingerprints to find the murderer, no Columbo closing in on court-accepted evidence. So what is this story, then?–I asked. What is it about? “It’s all about the main character’s madness,” one student replied.

“The Tell-Tale Heart” is first-person POV and stays with the same character through the emtire story. But the story doesn’t take place at the scene of the POV-character’s craziness and murder: it’s implied he’s telling us about what happened sometime later. He also keeps repeating that he’s not insane, and uses his narrative to attempt to prove it to us, the readers. “Hearken,” he says, “how calmly I can tell you the whole story.” Of course, each instance he brings up allows us to understand more and more how insane he really is. This story is actually so much a monologue in style, it could almost be shelved with the dramatic literature. And, of course, it is a classic example of the “unreliable narrator.”

When you pick up this story again (and other stories) for this week’s exercise, look at punctuation and typeface: these things make the sound of a character’s voice vivid enough to hand to an actor (in fact, it’s said that punctuation was invented as a system of cues for a reader-aloud to know when to pause for breath). Notice how many pauses the POV-character takes, and how long. Notice the length of their sentences, and if that changes. Look at use of font changes like italics or all-caps, for emphasis. Notice any spelling oddities to illustrate dialect. Your mind can take the theatrical cues from the text itself to create the sound of a voice in your head. Try reading passages aloud. This is especially prevalent in older works of literature (especially any that pre-dates TV).

Ways Established Authors cheat, Making it Unfair For the Rest of Us:

POV and POV shifts are some of the most difficult techniques for a prose writer to master–I myself have been know to switch out of POV without realizing it, driving not only myself but my readers nuts. My problem is, I’ve been a reader forever (since about 1 & 1/2 years old, before I could talk), and so I’m heavily influenced by classic and/or phenomenal authors who are allowed to mess with the rules because they’re so good at the rules themselves.* So I try something similar, and all I’ve done is create a sloppy POV. Here are some of my favorite unfair examples:

1.) Fritz Lieber, author of the Lankhmar adventures, goes into and out of the POV of both his anti-heroes, but usually no other characters. So there’s no author-as-narrator, but also no limitation as such to either Fafhrd’s voice or the Gray Mouser’s voice only. And then, to make matters worse, there’s often information given that neither character knows / is present for, so what the heck POV is Leiber using? He’s not making mistakes, is he?

Well, no, actually–Leiber uses a brilliant device for his involved-author-narrator in those cases: phrases like “They say the two heroes did such-and-such, but but historians still argue,” or “For a while, the twain pass out of record, but by piecing together events, one can surmise…” In other words, Leiber’s involved-author voice is actually the POV of a group: the gossips and historians of the city. “They say,” or “Have you heard?” takes care of what would otherwise be either cumbersome POV shifts, or the inclusion, on and off, of an omniscient author-narrator. This way, we stay firmly within the world.

2.) Peter S. Beagle’s incredible novel The Innkeeper’s Song has chapters titled by character name, so it’s easy to see who we are supposed to “be” during that chapter. Faulkner does this too. And depending on what’s happening, he chooses which character should relay what information, so the various perspectives on sometimes the same events not only paints each character more vividly than a limited-1st, but also reveals secrets with the most emotional impact.

3.) Douglas Adams’ Hitchhiker’s Guide series (especially the first one) has an involved omniscient author POV too, but instead of it being the author’s voice (a-la Dickens), the POV is that of the Guide itself, sort of a PDA of all possible information in the galaxy one might need (and much that one doesn’t). Using this mechanical “character” as the involved omnisceint author, we get some hysterical dry humor, at times almost a MST3K-like commentary on events.

4.) YA novel Mara, Daughter of the Nile does the whole-chapters-in-different-POVs to good effect. It’s a thriller/suspense novel set in Ancient Egypt, and who the POV is at any time is crucial to the suspense: in a mystery or a thriller, when a reader knows a thing is more important than what she knows. Author McGraw also totally cheats: a couple scenes are in the POV of the egyptian goddess of the night and childbirth, Nuit. Nuit is not involved emotionally or vitally in the events taking place, but can literally look down on the characters and what they are doing, relaying information in a very detached manner, instead of a rapid POV-switch.

As you skim your favorites noticing POV, see how and why these authors do what they do. See if you can mess around within your own fiction: see where you get too cinematic, where you shift POV, if you can tell, and if you should. Try limiting yourself to just one of your characters’ POV for a while, see if it changes your intimacy with the character, if he tells you more about himself than you knew before.

*It was the illustrator Hirschfeld who said something about the only reason he could represent, say, an arm with only one curved line was because he knew exactly how to draw the arm with anatomical accuracy first.